livejournal taught me how to gossip

On writing and subliminal messages and bitching and Substack.

I am quite an obsessive person and I write a lot and I read a lot. And when I read things I like I want to annoy everyone in my WhatsApp contacts to do a close reading on why it’s good (similarly, when I read something I hate I want to annoy everyone in my WhatsApp contacts to do a close reading on why it’s bad). Unsurprisingly this is not conducive to good and healthy friendships. Luckily the parasocial relationships you get through internet newsletters are inherently neither good nor healthy, so I don’t have to worry about this here. And by here I mean: a weekly Substack where I share the things I’ve read and liked and write things which exceed the tweet character limit and have no business being in other publications.

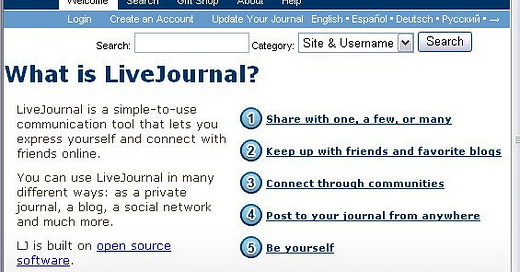

Although there are plenty of Substacks I read religiously – here are a few of my favourites – it wasn’t until I started thinking about doing my own that I considered where this sort of writing had existed on the internet before. Sometimes people compare this kind of writing (unfavourably and unkindly, usually when they are talking about someone they don’t like) to journaling or the XOJane personal essay genre that infested the internet of the mid-2010s, I see it as more similar to LiveJournal. As a tween – here I am dating myself as somehow pre-historic – me and my friends, who were all nerds of varying degrees, adored LiveJournal, which was basically nascent personal essay blogging for a pre-social media world. We had MySpace and Bebo, and later Facebook, but it was LiveJournal where we’d go to dump all our thoughts and gossip and accounts of the days we spent together shoplifting bottles of Boost to mix with Glen’s vodka outside Belfast City Hall (as well as being nerds, we were also mainly goths, and for us this was where local goths did local goth things). LiveJournal was how we stayed connected to each other but it was also where we learned to write in a coded, barbed way at each other. We put poorly written subliminal messages in there, about people we fancied or hated, and then fought and talked endlessly about what it meant. You would think writers grow out of this practice, the way the internet grew out of LiveJournal. I don’t think that’s the case though.

Recently I have been thinking about how writers write about other writers. And then wait to see if they notice. Which is a very silly and pathetic game really. This game does not have to take the form of subtweets or newsletter writing, even. A few Saturdays ago I was in a very hot underground bar in Chinatown with a friend from work (writing) who is friends with another writer who recently wrote about their relationship (with another writer). “Did you read the article?” I am roaring at my friend over the noise of the music, which is supposed to be ambient and does not feel ambient. He shakes his head and finishes the £10 Margarita we just queued for 20 minutes for. “Fuck off”, I say. “But it’s about -” “No I know” “Did they read it?” “No but they read the last one.” “I did think it was probably intended for them to read it.” “Why?” “So they could start talking again.” “Are you saying it was a beg?” “Kind of. I also thought it was really similar to that column from -” “Yeah I thought so too.” “Do you think they’re annoyed?” “Nah, they shared it on Instagram.” “Yeah I saw that. I mean they’re friends.” “Yeah.” We stop then because we’re both hoarse and thirsty.

It doesn’t have to be as personal as this either. Last year I spent an embarrassing amount of time gushing about an article I’d enjoyed on a very dry topic to someone who waited until I was done to inform me that it was published as a way to get someone the writer knew to sleep with them (this person presumably also enjoyed the very dry topic). It’s kind of worse if you know the semi-backstory to these weird ploys, if you can spot them. It can sometimes feel like you've been cheated somehow, by not spotting it. Or it cheapens the experience of liking something you've read, because now you know how it's been created and why. Sometimes I read a veiled reference to someone I know or kind of know in someone I know or kind of know’s column or op-ed and feel embarrassed on their behalf. It feels a little like watching someone be ghosted in real time, or rejected at a house party, but less fun and somehow more messy. If it sounds like I’m immune to this practice – even though I am writing about other people doing it, in a Substack – I’m not! Recently a very vague, pseudoaccidental reference to a night out with me appeared in another writer’s column and I was so furious about this infringement on my privacy I instantly messaged them and shouted at them about it until another friend (again, writer), told me how stupid I was being. I spent all day reading the replies to this piece on Twitter and decided I would never do that to someone. Two weeks later I had an essay which had incredibly thinly veiled references to people I knew in real life accepted by a literary magazine, and changed my mind.

All writing is probably essentially a beg for attention. But in communities or social circles of writers, it becomes more acute; more convoluted, more narcissistic, more intolerable, and more funny. Articles become the crafted, monetised version of Instagram stories of sad Spotify songs, or a sudden increase in post-break up selfies. The audience withers down to five or three or one. It becomes a snake eating itself situation.

I’m not sure how this applies to launching a weekly newsletter about writing. Maybe I need to find friends with different jobs.

This week I liked:

Wild Geese by Soula Emmanuel, which came out at the end of March, is fantastic. I can’t stop underlining bits I like while sitting on the Overground, which is very undignified. Last week Barry Pierce went to Dublin to speak to Soula for i-D, and Donal Talbot shot some lovely photos of her with a sculpture of a big blue hand.

I’ve never read A Little Life, but I’ve read endless harrowing reviews of the West End adaptation, which feels like enough? Eloise Hendy mourns the age of misery lit.

Tim Jonze’s moving piece for The Guardian on being diagnosed with cancer as a young person addresses something that has sadly been historically overlooked in sickness or cancer writing, I think; how it continues to impact your life long after the dust has settled.

And in the spirit of gossip & tech: Jonn Elledge on how WhatsApp has us in a chokehold (those blue ticks cause me deeper psychological despair than I’d like to admit).

This week I wrote about: how local news in the UK is broken, and why (of all things!) curated, email newsletters might be the answer, for Prospect’s May issue, and collated some of the best non-fiction books coming out this year, for i-D.